2022-04-23T11:42:00

There was nothing to do at home, so I went out.

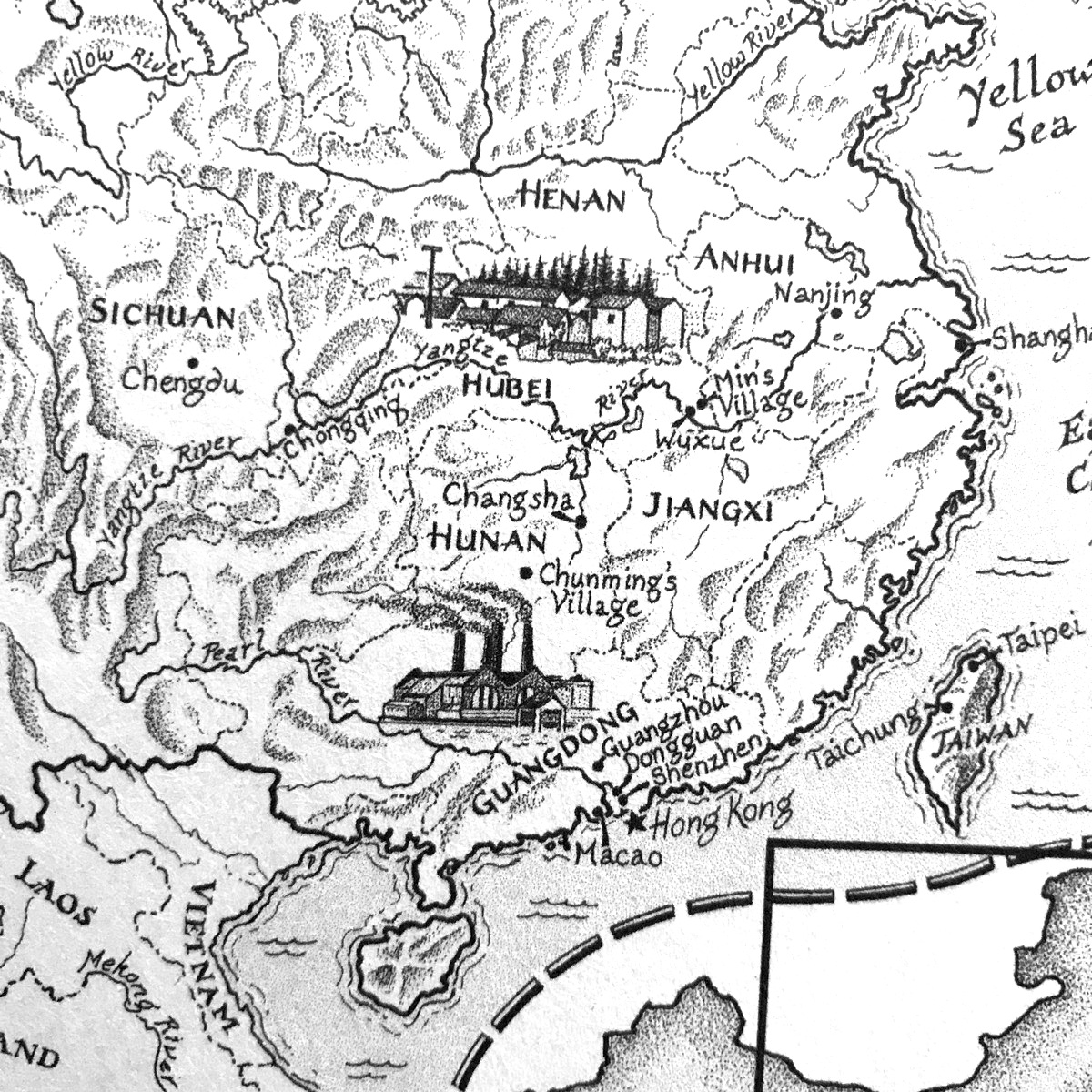

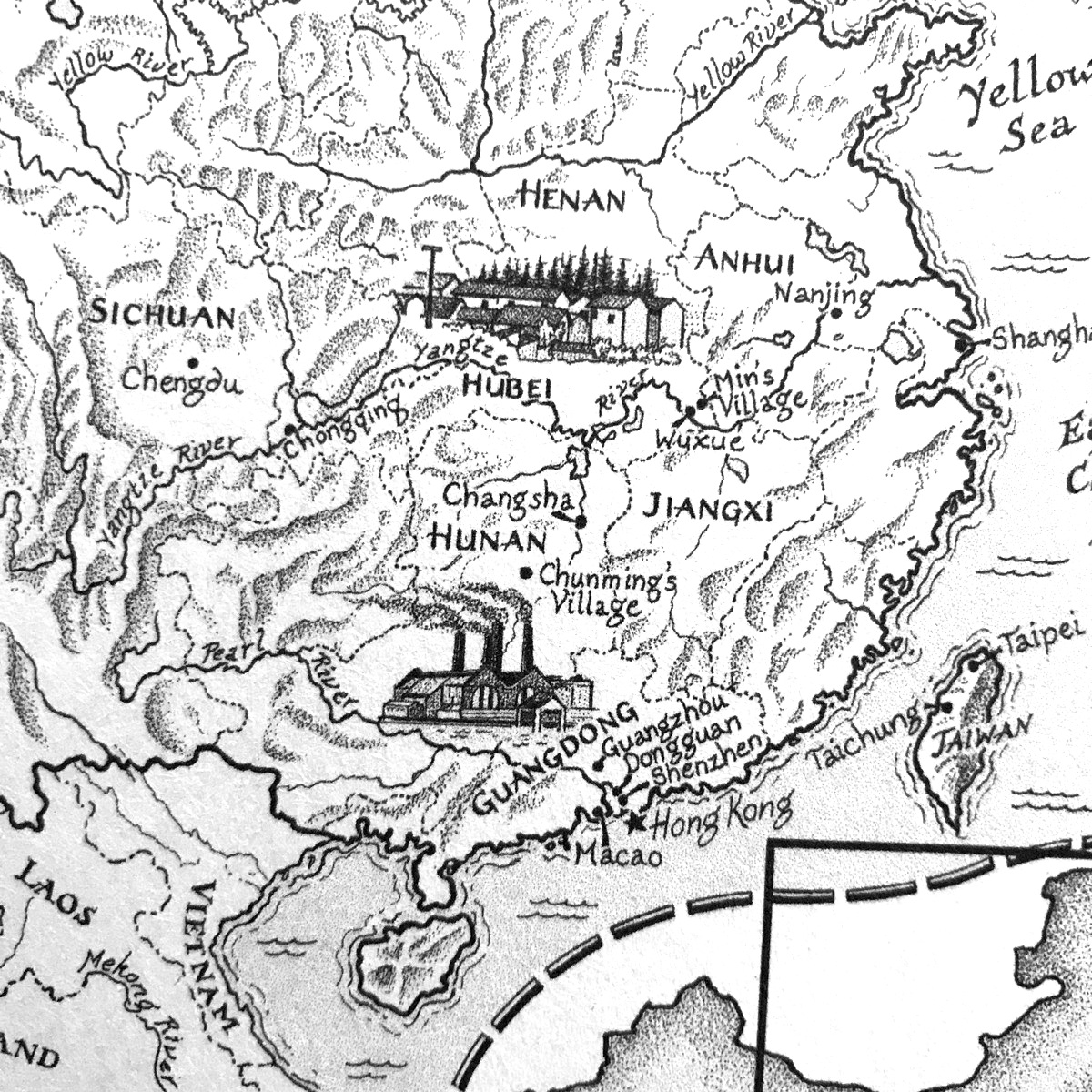

Here are my notes from book "Factory girls - voices from the heart of modern China" by Leslie T. Chang who reported about lives, motivation and moods of people leaving their home villages and towns (migrants) to start and earn a new life in industry zones of China.

- p4 Getting into a factory was easy. The hard part was getting out.

- p11 Migrant workers use a simple term for the move that defines their lives: chuqu 出去, to go out. There was nothing to do at home, so I went out.

- p12 Most of today's young migrants don't come from the farm: They come from school. Farming is something they have watched their parents do.

- p16 On the day we met, Min told me her life plan. She would work in the city for seven years, sending money home all the while to repay her mother and father for raising her to adulthood; that reflected the traditional Chinese view that children should be grateful to their parents for the gift of their existence. When she turned twenty-three, the debt repaid, Min would return home and find someone to marry.

- p25 The assembly lines of Dongguan, one of the largest factory cities in China, drew the young and unskilled and were estimated to be 70 percent female.

- p27 American and European bosses treated workers best, followed by Japanese, Korean, Hong Kong, and then Taiwanese factory owners. Domestic Chinese factories were the worst, because "they always go bankrupt," one migrant explained to me.

- p27 Many things I had read about China's migrants were not true. They no longer lived in fear of being picked up by the police; instead, the authorities just ignored them. Discrimination from local residents was not really an issue, because migrants almost never encountered locals.

- p27 I came to like Dongguan, which seemed a perverse expression of China at its most extreme. Materialism, environmental ruin, corruption, traffic, pollution, noise, prostitution, bad driving, shot-term thinking, stress, striving, and chaos: If you could make it here, you'd make it anywhere.

- p28 Dongguan was also a city of contradictions, because modern Chinese history had begun here. During the nineteenth century, British smuggling of opium into China devastated the country and drained the treasury. In the simmer of 1839, a Qing Dynasty imperial commissioner named Lin Zexu ordered the public incineration of twenty thousand cases of opium in the harbor at Humen, a town in Dongguan. The act set the two nations on course for the First Opium War, which was fought in Guangdong Province and ended quickly when British warships overwhelmed Chinese forces.

- p57 Young women - less treasured, less coddled - could go far from home and make their own plans. Precisely because they mattered less, they were freer to fo what they wanted.

- p66 The network-sales model was ideally suited to a Chinese society in which traditional morality had broken down and only the harshest rules - trust no one, make money fast - still applied. The companies relied on traditional networks of extended family and friends; the first thing a chuanxiao salesman usually did was to browbeat every friend and relative into buying something.

- p75 To me, every town looked the same. Construction sites and cheap restaurants. Factories, factories, factories, the metal lattices of their gates drawn shut like nets. Min saw the city through different eyes: Every town was the possibility of a more desirable job than the one she had. Her mental map of Dongguan traced all the bus journeys she had made in search of a better life.

- p78 Part of being a migrant worker was having no idea how to spend leisure time.

- p93 she was looking for a smaller factory with fewer superiors to please.

- p94 The boss smiled. "When you have to speak," he said, "you should speak. If you don't have to speak, don't speak." That was the secret rule of Chinese workplace survival.

- p103 The girls in J805 workedin the Yue Yuen Number 8 factory, which made shoes for Adidas and Salomon. Now they were working only ten and a half hours a day plus half or full days on Saturdays; in the world of Dongguan manufacturing, that was considered the slow season.

- p114 the head of Yue Yuen's manufacturing operations for Adidas in Dongguan: "We didn't talk about whether to pay overtime, or whether to put toilet paper in the bathrooms, or whether workers should wash their hands, or how many slept in each dorm. We used repressive management methods: This is your task and if you have to stay up three days and nights, you do it."

- p126 Perhaps in a world where so many people had suffered, one person's story did not matter. Suffering only made you more like everyone else. The young women in the factory towns of the south did not think this way. In a city untroubled by the past, each one was living, telling, and writing her own story; amid these millions solitary struggles, individualism was taking root. It was expressed in self improvement classes and the talent market, in fights with parents and in the lessons that were painstakingly copied into notebooks: Don't lose the opportunity. To die poor is a sin. The details of their lives might be grim and mundane, yet these young women told me their stories as if they mattered.

- p130 That he did not comprehend a word of these texts was unimportant; education was intended to shape a child into proper behavior, imprinting him early with the virtue of obedience, respect and restraint.

- p160 For more than a century, Chinese leaders and thinkers had wrestled with how to fit their traditions into the modern worlds. The cultural Revolution proposed a simple answer: Throw everything out.

- p167 But Chinese immigrants are different: No matter what terrible things happened to their families in China, they go back, on whatever terms the government allows. This is in part pragmatism that runs so deep that it excuses the past, but it is more than that. Chine to them is not a political system or a group of leaders, but something bigger that they carry inside themselves, the memory of a place that no longer exists in the world. China calls them home - with the weight of its tradition, the richness of its language, with its five thousand years of history that sometimes seems to be one repeating cycle of tragedy and suffering. The pull of China is strong, which is why I resisted it for so long.

- p180 In pursuing success, knowledge contributes 30 percent and interpersonal relations 70 percent.

- p183 "We are all in the sales business," the White-Collar teachers reminded their students again and again. "What are we selling? We are selling ourselves."

- p187 Her story was like all the migrant stories I had heard: Through speaking up and telling lies, she had risen.

- p190 Chinese people are bad at dealing with strangers; if someone doesn't fit into their known universe of family, classmates, or colleagues, the usual response is to ignore him.

- p190 In the course of the semester, every student had to give a speech introducing herself. These always started the same way: I am the same as you. It was a funny way for a person to begin her own story, and it wasn't even true. But perhaps it was only be establishing that she was part of the group that a young woman gained the courage to stand apart from it.

- p193 Her dilemma seemed to me distinctly Chinese. She had lied her way into her job, and then lied herself up the work ladder; she had no qualms about the truth. But now her boss was making her feel guilty about abandoning the group, and she seemed powerless to cope with that. In traditional Chinese society, maintaining harmony with others was the key to living in the world. The moral compass was not necessarily right or wrong; it was your relationship with the people around you. And it took all your strength to break free from that.

- p196 The man's name was Ding Yuanzhi, and not long ago he had taught high school physics. Hi book, Square and Round, was said to have sold six million copies. Now Ding Yanzhi toured the country teaching people how to manipulate their way to success as he had done.

- p197 I had always felt that social interactions among Chinese were needlessly complicated. Confucian tradition, which emphasized not the individual but his role in a complex hierarchical order, placed great value on status, self-restraint, and the proper display of respect. The Chinese had been living in densely populated communities for several thousand years, and they had developed subtle skills of delivering and detecting slights, exerting power through indirect means, and manipulating situations to their own benefit, all beneath a surface of elaborate courtesy. Even Chinese themselves often complained that living in their society was lei, tiring. I had not appreciated just how tiring until I read this book, which devoted eight pages to how to smile and forty-five pages to lulling others into letting down their guard.

- p202 Action was the only thing that set successful people apart.

- p209 Whenever I watched Chinese people interact in a group setting, I understood in my bones how the Cultural Revolution happened. People were terrified of being singled out, but from the safety of the group they could turn on someone with a speed and ferocity that took your breath away.

- p223 But she absolutely would not date anyone under 1.7 meters, because a man that short gave her no sense of security.

- p240 Ding Xia had worked at this club long enough to know. But most people moved in and out of jobs so quickly that to invent the past, along with the future, was easy enough.

- p252 In Dongguan, barely knowing something qualified you to teach it to others.

- p271 "Is your family poor?" she asked Ah Jie once. "Very poor," he answered. That was all she knew, and it was fine with her. "I don't want to know their family situation, and I don't want them to know mine," she told me. "In the end we must rely on ourselves."

- p274 Hierarchy governs village life: The older men, the chief decision makers in their families, choose what is best for the community too. A family eats and farms together, and at night the children discipline the younger ones, and the younger ones obey. Guests show up unannounced and stay for days; communal routines of eating and sleeping and, these days, television viewing absorb them easily. There are no secrets in the village.

- p275 Being Chinese has conditioned them to know that there will never be enough of anything.

- p276 Nobody on earth generates trash faster than the traveling Chinese.

- p280 …the hierarchy of the universe: heaven, earth, nation, parents, teachers.

- p289 Being considerate of others was not the village way: People spent all their time in groups, so they were good at ignoring one another.

- p290 The focus of village life was television. The children sat in front of the set all day; if you visited a neighbor, you were usually given a front-row seat where you could pick up the same episode you had been watching somewhere else.

- p293 The Chinese countryside is not relaxing. It is a place of constant socializing and negotiation, a conversation that has been going on for a long time and will continue after you are gone. Spending time in Min's village, I understood why migrants felt so alone when they first went to the city. But I also saw how they came to value the freedom they found there, until at last they were unable to live without it.

- p307 A family is not a piece of land. It is the people who belong to it, and it is the events that shape their lives.

- p322 The genealogy reflected the traditional Chinese view that the purpose of history was not to relate facts or record stories, but to establish a moral standard to guide the living. History was not simply what happened, but what ought to happen if people behave as they should.

- p361 In this society, a person who is too well behaved cannot survive.

- p406 "I don't mean to be a big scientist or something like that," Chunming said. "How many people can do that? I think if you live a happy life and are a good person, that is a contribution to society."

- p426 Migration in China has been going on for a quarter of a century because millions of people would rather try their luck in the city than remain subsistence farmers.

- p430 "Well, I don't want to burden people with this the minute I meet them. What if they don't know how to react?" I realize that's a very Chinese reaction.